|

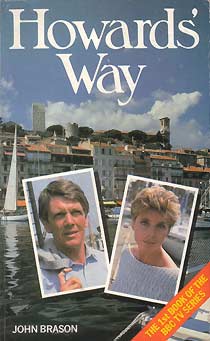

PRESS REACTION Compiled by Matthew Lee © 2005 WARNING - THIS GUIDE CONTAINS SPOILERS THE LISTENER - September 12th, 1985 Article by John Naughton Keyhole of Hell: The same could be said for Tom Howard, the eponymous hero of Howards’ Way (BBC-1), the latest serial on the lives and harassed times of the Jag-owning classes. The story-line is approximately as follows. Clean-cut, middle-40ish Howard (Maurice Colbourne) is a highly-paid aircraft designer who has just been made redundant. He lives in a very Sanderson villa on the South Coast with glossy wife Jan (Jan Harvey) and two happy, over-indulged kids. Tom’s one great love in life is sailing the boat which he designed, which is just an excuse for the cameramen to practise their Martini-advertisement shots. Fortunately, the sun always shines in BBC-1 serials about middle-class life, so the cameraman can always shoot into the sun. Just like the Martini cameramen do. Meanwhile, just down the road, ol’ Jack Rolfe’s boatyard is rapidly going bust, which is not surprising given that it is managed by Jack (Glyn Owen), who hasn’t had a new idea since 1908. He does, however, have a sexy, ambitious – and single – daughter, Avril (Susan Gilmore), who sees right through him. Jack offers Tom Howard a stake in the yard, in return for his redundancy money. This will, in due course, take Tom’s money to the laundry and his weary frame to Avril’s bed. For this is a Kentucky Fried Series, in which ingredients are selected by computer and blended in a Moulinex. Just to underline the point, Mrs Howard, who has the makings of a promising shrew, works for the local cad and lecher. You can tell he’s a bad because he drives a BMW. He, spotting that she cannot stomach the idea of losing life’s little luxuries, offers her a bigger job, and will have her in bed before she can splice a mainbrace, or whatever it is one does with mainbraces. Etc, etc. What’s objectionable about all this is not that it isn’t well done – in its way – but that it’s so safe and predictable. I can think of several series along these lines over the last three years – all centred on the idea of a middle-aged man’s sudden change of life or direction, and all mixing sex, money, Jags and BMWs in equal proportions. Who watches this stuff, besides television critics? Is it television’s answer to the problem of executive redundancy, encouraging sacked managers to abandon their marital couches and sink their golden handshakes in new enterprises – rather as the Ministry of Agriculture tries to encourage modern farming practices by having them mentioned on The Archers?

THE LISTENER - October 17th, 1985 Article by John Naughton Autumn Leaves: This autumn season is all very well for the rest of you, but for us critics it is bloody murder. I mean, you can just plug into the first glossy episode of a much-hyped serial and then tune out for the duration. You can sleep in front of the television, or read the memoirs of Ms Sara Keays, or write letters to your grandmother in a fine Italian hand. But we critics have to watch the damned stuff week in, week out, just in case something happens. Take Howards’ Way (BBC-1), for example, an everyday tale of the Jag-owning classes. Set in Hampshire-by-the-sea, where the sun always shines, and the yacht clubs are full of BMW-driving cads, and the middle-classes are so bored they even yawn while screwing one another, it features Maurice Colbourne as Tom Howard, a redundant aircraft designer with a passion for sailing boats and a nice line in craggy wholesomeness. Tom has sunk his lot into a bankrupt boatyard, lured in by the beautiful, sexy and ambitious Avril Rolfe (Susan Gilmore). Meanwhile, shrewish, upmarket Mrs Howard (Jan Harvey) works for the local lecher, who sees her as the bit of class he’s always wanted and plans to have her as such. From the outset, it was clear that they would all wind up in one another’s beds. It’s taking an age, though: they are not so much jumping into bed as crawling towards it, like a column of earwigs marching through treacle. The root cause of the problem is structural, namely that of too many sideshows chasing too few slots. There are simply too many subplots, too many “characters” to be developed, too much business to be transacted in the space of fifty minutes. Apart altogether from the matter of Tom Howard and the boatyard, for example, there is the impending affair with Avril, his partner’s affair with his mother-in-law, his daughter’s problems with yacht-club lechers, his wife’s impending flutter with her snake of an employer, his son’s search for fulfillment and organic food, not to mention Polly Urquhart’s relentless promiscuity, her husband’s homosexuality and her daughter’s quest for commitment.

THE LISTENER - November 14th, 1985 Article by John Naughton Bucket Cop: Thos who laid odds with me that Howards’ Way (BBC-1) couldn’t get any worse may now be seen wandering shirtless up and down the Marylebone High Street. Their great mistake was to underestimate the lengths to which scriptwriters will go when they’ve run out of ideas. The dramatic potential of Tarrant, Hants, having been temporarily exhausted, Mrs Howard (Jan Harvey) was dispatched to sunny Cannes, where she communed with Malcolm Jamieson, who played a joke Frenchman in the great tradition of Inspector Clouseau. She stayed in a bedroom furnished by Cecil B De Mille out of Louis Quatorze throw-outs before eventually succumbing to the greasy charms of Ken Masters (Stephen Yardley), the BMW-driving cad and lecher. “I’m frightened, Ken,” said she, before yielding to his hot caress, adding that she was a married woman, which Ken, being her employer, must have known already. “Do you know,” he replied, conversationally, “I love you so much it almost hurts”. This is the kind of thing that gives superficiality a bad name. The only thing to be said about Howards’ Way is that if all the viewers who sleep through it were laid end to end, they would be much more comfortable.

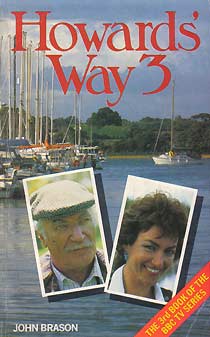

THE LISTENER - August 28th, 1986 Article by John Naughton Pneumatic Tryers: A would-be Hollywood starlet of pneumatic physique was once picked up from a casting couch by a big-time mogul who promised her a part in the movies if only she would remove her underwear. Having had his way with her, he then, in the time-honoured way of these things, tried to drop her, only to find that she had made a video of his performance, including close-up footage of acts which would constitute criminal offences in several states. Accordingly, he was obliged to make good his promises. The only trouble was that the lady had no acting talents at all; even walk-on parts were beyond her. So in desperation, the mogul bought into a travelling stage production of The Diary Of Anne Frank on condition that she got to play the lead. Her performance was such, a local newspaper critic claimed, that when the Gestapo finally came hammering on the door, the audience rose as one man and roared: “She’s in the attic, she’s in the attic!”. “Pshaw,” I hear you say, “he’s making that up. Nobody could be that bad”. Well, I got news for you, folks. For Howards’ Way (BBC-1) is back for another series, with a cast which makes our pneumatic heroine look like Joan Plowright. On the grounds that those who saw it before will have forgotten what it was about, last Sunday evening saw the screening of the last episode of the first series, in preparation for what is to come in the next. Here is the story so far. By the banks of the Hamble, deep in Gin and Tonic country, there is a colony of sailing folk who are permanently dressed as if about to attend a wedding. The “action” revolves around the Howard family, who are fundamentally nice people thrown by circumstances and without navigational aids into a maelstrom of sex, money and property development. Papa Tom (Maurice Colbourne), the eponymous hero, for example, sinks everything in a bankrupt boatyard, hoping to rescue it by bringing his engineering design skills to bear upon yacht design. Whereupon, he falls into bed with beautiful temptress Avril Rolfe (Susan Gilmore) who shivers his timbers no end. Meanwhile, wife Jan (Jan Harvey) has fallen into the erotic clutches of dastardly Ken Masters (Stephen Yardley) who drives a BMW and probably has a carphone and combines the looks of Edith Sitwell with the brains of Darth Vader. And the well-appointed daughter Lynne Howard (Tracey Childs), who likewise cannot resist a cad, is hopelessly in love with rich, unscrupulous Charles Frere (Tony Anholt). The last series closed with the distraught Lynne discovering Frere in flagrante with a corsetiered floozie and falling into the Hamble. The question is: did she survive? Only time and the next episode will tell, but my guess is that her aforementioned physique will not let her down. Or drown. The apparent success of this series suggests that British television is learning fast from the Dallas genre. Since the British super-rich – pace Fortune (LWT) – are not as spectacular as Texas oil families, the trick is to find a family setting for soap which is glamorous enough (in British terms) to attract the punters, but sufficiently culture-specific to be credible to the inhabitants of Huddersfield. The large crowds reportedly attracted by the filming of this new series, together with the appears of Jan Harvey on Wogan (BBC-1), suggests that the formula works, even if it leaves your critic lost for words.

THE LISTENER - October 16th, 1986 Article by John Naughton Tories Of Our Time: “It is not true,” saig a chap I once met in an autobahn Rasthof, “that the Germans are bad drivers. It is just that they hit everything they aim at”. I am beginning to think that the same kind of analysis should be applied to Howards’ Way, for, having started by assuming that a series so unutterably contrived, vulgar and unconvincing could only have been concocted by some ghastly accident, I am now convinced that the whole thing is intentional. That, in other words, the BBC department responsible for these things set about the task of devising a recipe which would maximise the audience “take” at eight o’clock on a Sunday night much as an earlier group planned and executed EastEnders to meet the Corporation’s manifest need for an answer to Coronation Street. The product which maximises the take in question is a glitzy soap, a tale of ordinary yachting folk told against the glittering backdrop of the Hamble estuary. Of course Howards’ Way caters to a different taste than does Coronation Street, just as EastEnders caters to a younger audience. In doing so, the saga of the Howard clan sheds some light on the changing social structure of Britain. Granada’s “street” is psychically rooted in the past, and is physically and dramatically located in the sunset zone – the wasteland North of Watford, with its decaying cities, derelict industries and the crisp-bloated inhabitants of Mrs Currie’s imagination. In contrast, both of BBC soaps are situated in the prospering South. Although EastEnders portrays the lower end of the social spectrum, its characters still live in a world of prospects, where prosperity lies just around a gentrified corner, if not within easy reach. And Howards’ Way completes the picture, by featuring the middle classes and the hard-faced men who have done well out of the recession and out of Mrs Hacksaw’s regime. If the BBC feels a need to reply to Mr Norman Tebbit’s allegations of anti-Tory bias, then I think the Corporation should simply point to Howards’ Way and then rest its case. For here are portrayed the Tories of our time, not as idle, bloated capitalists grinding the faces of the poor, but as ordinary folk going about their businesses of property development, apre-sail couture and capitalist reconstruction. (They do, of course, also climb in and out of one another’s beds rather a lot, but then so too do some of the Prime Minister’s favourites). As in a Tory party political broadcast, the central characters of Howards’ Way are seen as ambitious and resourceful people who take risks and mortgage their houses in order to expand businesses and provide jobs. And when – as in the case of the dreadful Ken Masters – they venture beyond the letter of the law, they are overcome with remorse, blame the villains they knocked around with in the dark days before everyone drove a BMW, and – most importantly – lose their shirts. It is hard to imagine a more moralistic tale. Or a less convincing one.

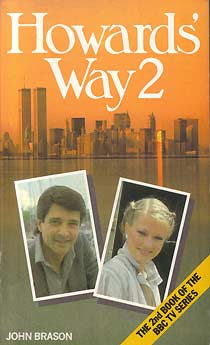

THE LISTENER - November 27th, 1986 Article by John Naughton The Fall Of The House Of Howard: It is always a mistake to open one’s mail. No sooner had I pointed out that Howards’ Way was the perfect answer to charges of anti-Tory bias in the BBC, on the grounds that it showed the Jaguar-driving, après-sail crowd in the best of all possible lights, than someone writes in triumphantly pointing out that everything had begun to go wrong for these glittering residents of gin-and-tonic country. “Explain that if you will,” crowed my correspondent. Well, of course, in one sense, she is right. Everything fell apart, the centre did fail under pressure, with fatal results. The Mermaid Yard was served with an enormous writ for damages. The Rolfes, father and daughter, did turn on Tom, suing him for negligence and worse. Abby did take up with a psychopath. And although Jan eventually saw through Dirty Ken, and found happiness with her pneumatic daughter and the latter’s pigtailed Frenchman, their cosy world was shattered by his cruel fate at the hands of a speedboat lunatic. End of (current) series. Now, on the face of it, these sad events might be seen as evidence of a radical determination to show that, in the end, the Jaguar-driving classes get their just desserts. But we structuralists are not content with such superficial interpretations. For one thing, there is the small problem of ratings to be considered. It transpires that Howards’ Way is exceedingly popular with the punters, for reasons which defy explanation. Accordingly, there will be further series, for which vast audiences are expected – and required. It was therefore necessary to conclude the present run with a veritable avalanche of catastrophies to whet the audience’s appetite for what comes next. Much the same formula is regularly used by Dallas and Dynasty – the latter going to the extreme of massacring the outgoing cast at the end of the last series. But this is merely a dramatic device in order to ensure continued interest in the follow-on series, in which no doubt Tom will claw his way back from bankruptcy and into Avril’s bed, Jan will rebuild her shattered fashion business and Lynne will find consolation as a model for wetsuits or, possibly, airships. And the underlying message of all this? Why, it is that capitalists are resourceful, tough, resilient folk who come back from the dead. Just like Mrs Hacksaw says they are.

THE LISTENER - May 12th, 1988 Article by Libby Purves Schlockwatch – Howards’ Way: I have these very high ideals about television. A window on the world. A sacred trust. Attenborough, gorillas, Newsnight, Cathy Come Home, Blue Peter. There is a great deal of rubbish around, one admits that: but nobody is physically forced to watch cop shows or Henry Kelly. One picks and chooses, does one not? The Discriminating Viewer, one is … So what am I doing, week after winter week, refusing invitations and fretting about video timers, bundling children early to bed, taking telephones off hooks and microwaving bagfuls of orange gunk, merely in order to become an immobile couch-potato, transfixed by Howards’ Way? How can I, who proudly boasts of never having seen Joan Collins moving, be enslaved to this inexcusable Anglo-Dallas, this hollow, hangling melodrama of showdowns and shoulder-pads, where birth and death and ruin are all met with the same set of facial tics beneath immaculately unswept eyeshadow? Why do I mourn when it goes off the air after each series, and why – like a heroin addict putting up with methadone – do I unerringly plug myself in to anything which feels a bit like it, such as the equally mad, overdressed, hectic and unbelievable Campaign? What have they done to me? I suppose I first watched Howards’ Way for the sailing. We like boats, in our house, and the ones we normally encounter seem to be crewed by nice middling sort of people, like waterborne Archers. You know, people in grubby sweaters, with children and dogs. Indeed, I wondered how on earth they were going to get any human drama out of the ruck of yachtspeople, since in real life we tend to be extremely level-headed, tea-brewing people, our cosiness compensating for the stagey howling of the wind and sea beyond the harbour wall. But Howards’ Way, it turned out, is not really about boats at all. It is about boardrooms and beds. The first series, in case you missed it, was a simple tale about Tom – a graying aircraft-designer with as House And Garden lifestyle – who blows his redundancy money buying into a ratty old boatyard run by a lovable alcoholic; there is his estranged wife, Jan, who rapidly turns into a womenswear tycoon; their adult children, Lynne the pneumatic blonde and Leo the Friend of the Earth; a frightfully wicked entrepreneur called Charles Frere who seduces maidens and bulldozes marshes, and other assorted inhabitants of a very uppity little town on the River Hamble, called Tarrant. We were charmed from the outset. Not only did all the female characters change their costume and blusher for every scene, but the sailing shots – considering that their technical adviser was lying on the cockpit floor, steering desperately from underneath – were a miracle of ham art. Tom Howard, in particular, had a knack of clutching the tiller while fixing the horizon with a steely gaze as if there might be an autocue out there somewhere. Lynne would haul in the spinnaker by the novel method of running the rope sensually across the top of her bare, bronzed thigh, yet it never left a mark. Back in the boatyard, the cast would saw away frenziedly for hours at very thin bits of wood, and deliver themselves of wonderful technical speeches. These went something like: “Got time for lunch, Tom?” “No – I’m supervising the installation of the stringers on the new design, using the new West Epoxy system lately developed in California”. Or: “Jack – I’m telling you – this new Polyurethane Foam Sandwich Construction is the way forward for us! It’s the Future!”. Meanwhile, characters climbed almost absentmindedly in and out of one another’s beds, as if searching for the ultimate Foam Sandwich partner. The series ended with Lynne fleeing down the marina pontoons from her faithless tycoon lover, biffing her head on a mooring-cleat and falling senseless into the briny. They left her there for eight months. Suspense mounted, or not. Eventually, the series came back with an amnesiac Lynne and a hilarious French fashion designer called Claude Dupont. By the end of the second series, Claude (pronounced Clod) had been minced up in a powerboat propeller after founding a fashion empire with Jan, who had by this time left the bed of the balding-but-sexy yacht chandler Ken, who instead was busy knocking off his new partner’s wife. Meanwhile, Abby (did I mention Abby? The pregnant one?) turned out to be the bastard daughter of none other than – gritty, grit, tic, tic – Charles Frere, the baddie! Scenes are frenetically intercut, to prevent the listener rolling off the sofa in paroxysms of laughter or grief, or perhaps because the cameras had perforce to swing rapidly away from the actors before they, too, collapsed. There is a lot in this latter theory: I had the pleasure of actually meeting Maurice Colbourne, who plays Tom Howard, and finding him to be a perfectly serious and decent actor, classically trained in the tradition of truth-to-life; he was very loyal to his scriptwriters, but mentioned in passing that there is, among actors in such productions, an accepted way of handling certain particularly dreadful lines (“Jan, Jan – we’re drifting apart, aren’t we?”). What you do is to distract the audience from the words with a bit of business. “You twitch your hair, or move your cup rather loudly”. Characters change radically from series to series – Charles Frere mutated from arch-bastard to victim of a tyrannical father, Leo Howard somehow managed to stop being a Friend of the Earth and became a pollutant wet-bike salesman without a word of remorse. Yet despite this blatant cheating, the plots can be seen coming: as they round each corner, their monstrous misshapen shadows are cast before them. If someone is going to commit suicide, you get special close shots of their eyes to warn you. If a man is going to be killed, you can be quite confident that he will leave an illegitimate daughter or a vengeful wife to mess up his business empire. The joy of this sort of schlock-drama is that anything could happen to these frightful people, and the viewer does not care: pity and terror are entirely suspended. When Claude was minced and Lynne widowed, we merely admired the gelatine tears and hummed along with the closing music. If you are the sort of concerned viewer who frets nightly about Nicaragua and the ozone layer, this is very therapeutic; there is a fearful, guilty joy in being harmlessly callous, just for an hour. These people are far too nattily dressed to attract sympathy. One laughs and turns down the thumb, like a Roman emperor. |

|

|